After the previous introductory post on mouldings, this and the next several posts in this series will examine the various basic moulding profiles, their uses and effects.

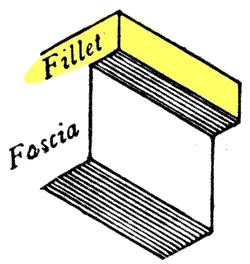

Moulding profiles can be grouped into four general categories: flat, convex, concave, and compound. The fillet and the fascia are the only common flat mouldings; they both present a flat vertical face that may be either raised forward of the supporting wall or sunk into it (then also sometimes called a channel). The distinction between a fillet and a fascia is only one of proportion: the height of the fillet face is typically equal to or only slightly greater than its projection/recess, whereas the fascia is much taller in relation to its projection.

These mouldings produce very sharp shadows. The shadow produced by a sunk fillet is ‘in’ the fillet itself, and is more intense than the shadow produced by a raised fillet, which appears below it. In this case the height of the shadow line varies in proportion to the depth of the fillet projection.

The lighting effects produced by fillets can be modulated in several ways: tilting the face back slightly makes it lighter than the background plane; tilting it forwards darkens the face relative to the plane. Rounding or bevelling the edges of the fillet softens the shading transition at these edges. The top surface of a raised fillet and the bottom surface of a sunk fillet may be given a slight fall, to better shed water and prevent accumulation of dirt.

In classical architecture, fillets and fascia are almost never used in isolation but as auxilliary elements that function to punctuate moulding compositions and define their edges, delineate curves, and give ‘spine’ to the overall composition. When used alone, they can have a stark effect; the sunk fillet in particular was employed to this end by modernists such as Mies to delineate elevator doors and the like.

Though the more complex curved and compound mouldings have mostly fallen out of favour, being perceived as too ornate, too costly or too ‘old-fashioned,' the fascia and the fillet are still in common use, thanks to their simplicity and utility. The fascia in particular is mostly known today as the timber board used to protect the end grain of projecting rafters and support the eaves gutter, and as the simplest profile of skirting board and architrave.

Skirting board with fascia profile

Architrave with fascia profile