Seating positions around the irori have long been determined by convention and formally assigned. Interestingly, though there are regions in which these seating conventions gradually weakened over time, and those where they are (or were) strictly maintained, there is very little variation observed across the country in regards to who sits where. In contrast, while the seating assignments themselves have been highly stable across time and place, the number of dialect variant names for them is huge, so this post will be as much etymological as anything else.

The highest ranking position around the irori, marked ‘1’ in the images, is the uppermost seat (jо̄za 上座), the one on the ‘interior’ side furthest from and facing the doma. This is the place occupied by the master of the house. It affords the best view of the dwelling’s entrance, whether that be in the façade (typically the long side) or the gable end (short side) of the building. It is the most favourable position for observing and giving orders to family members and employees undertaking activities in the ‘kitchen’ (katte 勝手) and doma (土間), and for keeping an eye on the condition of the animals in the stable (umaya 厩), among other things. The most common name across Japan for the master’s seating position is yoko-za (横座, lit. ‘side seat’), so called because a tatami mat or other sitting mat (goza ござ) was laid beside (yoko 横) the irori here. Other names include teishu-za (亭主座, ‘husband seat’), danna-ido (丹那いど ‘husband place’), and oya-zashiki (親座敷 ‘parent zashiki’). The custom of the ‘active’ master of the household sitting in this uppermost position appears to contradict modern practice, but it stems from the belief that the master of the house was the ‘priest’ of the guardian deity of the household, and is thought to trace back to ancient times, predating the etiquette of the feudal period. Therefore the heads of families of ancient lineage and the priests of family temples relinquish this seat, but Kawashima Chūji’s own father did not, occupying the position even after retirement: the only others who would be suffered to sit in the yoko-za were deemed to be ‘cats, fools, and priests’.

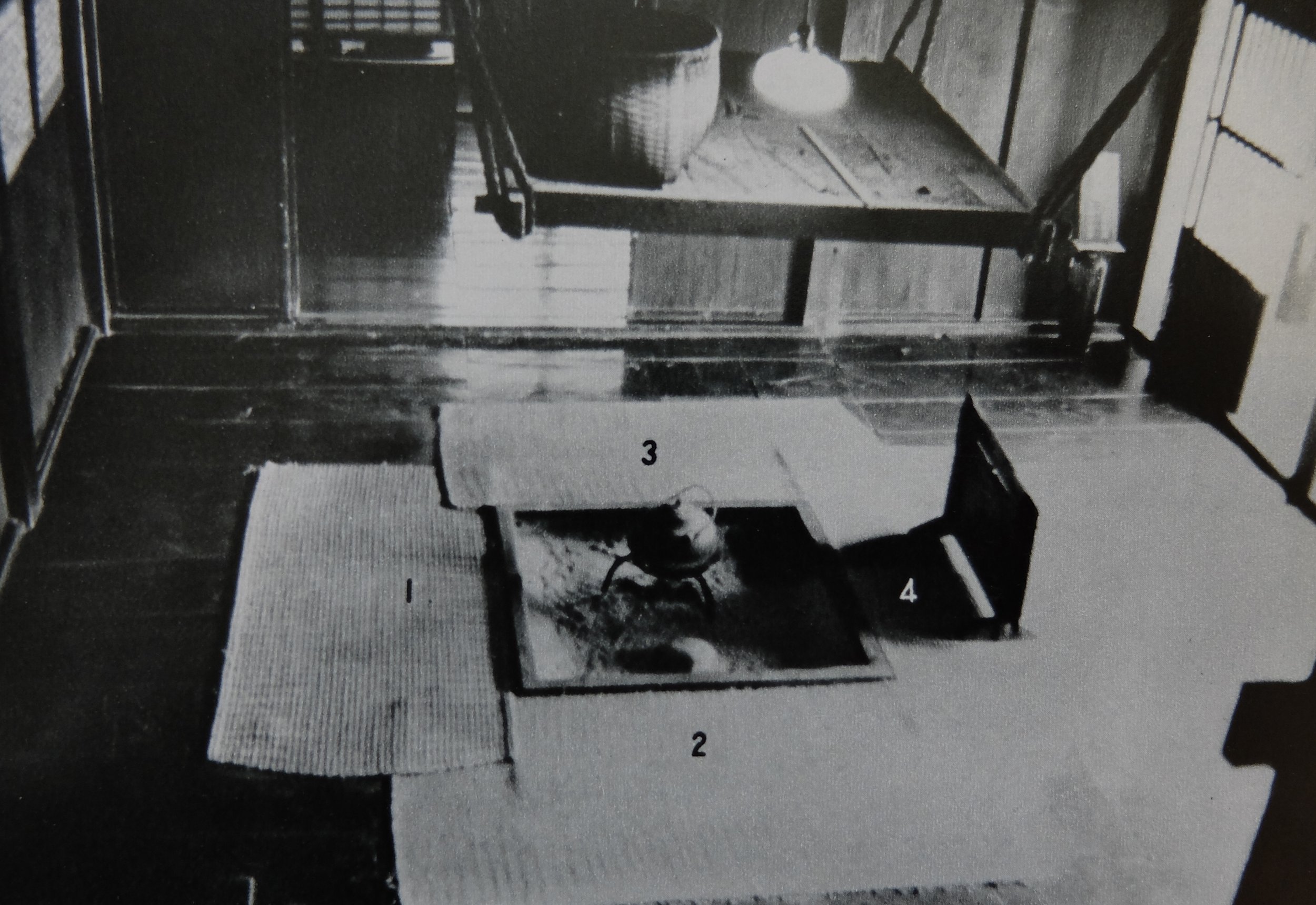

Seating positions around the irori (炉). Top (1), the ‘formal room side’ or ‘habitable room side’ (zashiki-gawa 座敷側), usually called the yoko-za (横座); at right (2), the rear/back side or ‘back door side’ (sedoguchi-gawa 背戸口側), usually called the kaka-za (嚊座); at left (3), the facade/front side or ‘door side’ (toguchi-gawa 戸口側), usually called the kyaku-za (客座); and bottom (4), the ‘doma side’ (doma-gawa 土間側), usually called the ki-jiri (木尻).

The second-ranking seat, marked ‘2’ in the photographs, near the kitchen (勝手 katte) at the rear (opposite to and farthest from the façade side) of the dwelling, is the women’s seat, centred around the wife (shufu 主婦). If the house faces south, this position is on the north (kita 北) side of the irori, so is sometimes called the kita-za (北座), but it is most commonly called either the onna-za (女座, lit. ‘woman seat’) or kaka-za (嚊座; kaka 嚊 means ‘to breathe through the nose’, ‘snort’, and by extension ‘wife’, ‘one's old lady’). The grandmother and daughters also sit in this position, lined up below (on the doma side of) the wife. Other names for the position include kaka-zashiki (嚊座敷 ‘old lady zashiki’), nyо̄bо̄-ire (女房入れ ‘wife container’), onna-jiro (おんなじろ ‘wife place’), uba-za (うばざ ‘granny seat’), baba-zashiki (ばばざしき ‘granny zashiki';), merojiya (めろじや ‘woman place’), and kami-san-zashiki (かみさんざしき, ‘god zashiki’). Because this is the position from which the wife serves meals, etc., there are also many names for it that relate to eating (ke, 食): keza (けざ ‘eating seat’), kedoko (けどこ ‘eating place’), kedomoto (けどもと ‘eating origin’), kenza (けんざ ‘eating seat’) kegura-za (けぐらざ), and mikenza (みけんざ); also nabeza (なべざ ‘pot seat’), nabejiro (なべじろ ‘pot place’), tanamoto (たなもと), chani-za (茶煮座 or 茶煎座 ‘tea boiling seat’), cha-in-za (茶飲座 ‘tea drinking seat’), cha-no-za (茶の座 ‘tea seat’), chai-no-za (ちゃいのざ ‘tea seat’), tane-za (たねざ), yaze (やぜ, from yashinau 養う ‘to nourish or nurture’), bonshi (ぼんし ‘meal’), and so on. Alternatively, as the place from which the wife feeds the fire (taku 焚く, ‘to kindle/boil/cook’), the seat may be called 焚座 (ta-za? or taki-za?), omo-hijiri (主火尻 ‘main fire bottom’), etc.

Finally, because the wife’s seat was the place from which she would keep a close eye on the master’s sword, laid beside him (on his left), it was also called koshi-moto (腰元, female servant, lit. ‘hip origin’).

In farming families, the agricultural work undertaken by the wife was as important as that done by the husband, and she also presided over the housework, so her seating position was not considered ‘low’ in status.

Plan showing a common location for the irori (炉) within the minka, in the main habitable room or ‘living room’ (here the hiroma ひろま) in the house. Position 1 at the irori is to its left; position 2 is above it; position 3 is below it; and position 4 is to its right. The ‘kitchen’ of the dwelling is the area above the dot-dash line.

The third-ranking seat, across the irori from the wife’s seat and nearest the (façade) entrance, marked ‘3’ in the photographs, is the position for guests or visitors, so is called kyaku-za (客座, lit. ‘guest seat’); when there are no guests, it is the seat for the men of the family other than the master, so is also called otoko-za (男座, lit. ‘man seat’). The woman seat and man seat were also called the tate-za (竪座), from their relation to the yoko-za; tate (竪) is the antonym of yoko (横) and is generally used to mean ‘vertical’, ‘standing’, etc. In the same way, the kyaku-za was sometimes called the ‘minami-za’ (南座, lit. ‘south seat’) in opposition to the wife’s kita-za, or the mukо̄-za (向う座, lit. ‘across seat’). It was also called yori-tsuki (よりつき), yori-tsuke (よりつけ), and yori-za (寄座), all derived from the verb yoru (寄る ‘to drop by’, ‘to visit’) and the compound verb yori-tsuku (寄り付く ‘to approach’, ‘to come close’). Other names that relate to the seat being that of the guest (kyaku 客) include kyaku-ro (きゃくろ ‘guest place’), marito-za (まりとざ, from mare-bito 稀人, an incorporeal visitor from the otherworld), hito-zashiki (人座敷 ‘person zashiki), hito-za (ひとざ ‘person seat’), etc.; also, because it is the seat of the bridegroom (shinsei 新聟, lit. ‘new son-in-law’) it is called the muko-za (聟座 ‘son-in-law seat’), ani-za (兄座 ‘older brother seat’), etc. Names that derive from the position being the otoko-za include otoko-zashiki (男座敷 ‘man zashiki’), otoko-ire 男入れ ‘man container’), otoko-jiro (男じろ ‘man place’), and so on.

View of the irori from the doma, with the four seating positions labelled: the yoko-za (横座), corresponding to (1) in the images; the kaka-za (嚊座), corresponding to (2); the kyaku-za (客座), corresponding to (3); and the ki-jiri (木尻), corresponding to (4).

The fourth position, marked ‘4’, across from the yoko-za and adjacent to/at the edge of the doma, is the lowest-ranking seat, and usually goes by shimo-za (下座 ‘lower seat’) or ki-jiri (木尻, lit. ‘tree/wood tail’). The seat of employees and ‘casual drop-ins’ or those not high enough in status to sit at the kyaku-za, it is also called matsu-za (末座, lit. ‘end/trivial seat’), shimo-jiro (しもじろ ‘lower place’), shimo-iri (しもいり ‘lower container’), ge-sui (げすい), and dekansa (でかんさ, from the meaning of ‘employee’). As it was not used by family members it was also called ake-moto (あけもと ‘empty place’). As the position from which the fire was fed, the seat might be called hota-jiri (榾尻 ‘woodchip tail’), takimono-jiri (焚物尻 ‘firewood tail’), ki-no-moto (木の元 ‘wood place’), or ki-jiro (木じろ ‘wood place’); ki-jiri itself belongs to this group of names. Due to the many taboos applying to young brides (yome 嫁), this was often the only position in which they could sit, and so it is also called the yome-zashiki (嫁座敷 ‘wife zashiki’). Where the wife sits, so children and cats gather, so the position is also called ko-ido (こいど ‘child place’), ko-mochi-jiro (子物じろ ‘child holding place’), ako-jiya (あこじや ‘baby place’), neko no yoko-za (猫の横座 ‘cat yoko-za’), neko-no-ma (猫の間 ‘cat space’), neko-zashiki (猫座敷 ‘cat zashiki’), etc. Some of these names display a folk humour and irreverence that is not seen in the names for the other positions, with the possibly tongue-in-cheek exception of kami-san-zashiki.

For the convenience of being able to step into the irori without removing footwear, there are irori with the ki-jiri-za side partly cut away or entirely omitted, and those where the width of the ki-jiri-za (the distance between the edge of the irori and the room-doma edge is narrowed (the irori moved closer to the doma) with a moveable wooden platform called a ki-jiri dai (木尻台) placed in the doma up against the edge of the floor. There are places where the shimo-za goes by the strange name kinsuri-za (きんすり座), because when the ki-jiri dai is moved aside, those tending the fire from the doma would rub (suru 摺る) against the edge of the floor.

Example of an irori without a fixed ki-jiri seating position: the doma side of the irori is fully open to the doma. There is a low, gapped-board clad (sunoko-bari 簀の子貼り) ‘fire-side platform’ (hijiri-dai 火尻台) at the open ‘fire side’ (hijiri-gawa 火尻側) of the irori.

A girl standing on the ki-jiri dai set in the doma up against the narrow ki-jiri side of the irori. Note also the kindling piled next to the ki-jiri, and the cat.

The seating positions at the irori, and their many names, reflect the domestic and familial order that grew out of the high-low and master-servant status systems and distinctions of the feudal period; but, as we have seen, they can also be said to have a rational basis, when considered from the point of view of everyday life and the practical considerations and demands of the dwelling.

Seating at the irori. 1) the yoko-za (横座, lit. ‘side seat’). 2) the kaka-za (嚊座; kaka 嚊 means ‘to breathe through the nose’, ‘snort’, and by extension ‘wife’, ‘one's old lady’). 3) kyaku-za (客座, lit. ‘guest seat’). 4) hijiri-za (火尻座, lit. ‘fire bottom/buttocks seat’), the side of the irori on which firewood and kindling is stored and from which the fire is fed. From the residence of the Takeda family (Takeda-ke 武田家), Tokyo Prefecture.

A large irori 太炉 in the ‘living room’ (oe おえ) of a Gasshо̄-zukuri minka in Gokayama district (五箇山地方) of Toyama Prefecture, the residence of the Murakami family (Murakami-ke 村上家), an important cultural property. To the rear of the yoko-za (1) is a chо̄dai-gamai (帳台構え), a formal entrance to a bedroom.

Seating at the hearth in the ‘formal room’ (dei でい) is not strictly determined/absolutely fixed; here the positions of the kaka-za (2) and kyaku-za (3) are reversed in relation to the layout of the room. The former residence of the О̄i family (О̄i-ke大井家), originally Gifu Prefecture, now relocated to the Open Air Museum of Old Japanese Farmhouses (Minka Shūraku Hakubutsukan 民家集落博物館) in Toyonaka City, О̄saka Prefecture (豊中市大阪府).