Last week’s post briefly touched on the man-made waterways (yо̄suirо 用水路, lit. ‘use water road’) - the irrigation waterways, canals, ditches, charged gutters, and so on - that are ubiquitous in Japan. Before the introduction of underground reticulated water supplies, these yо̄suirо served as a source of domestic water for many households, particularly in urban areas. The water drawn off from them was called tsukai-gawa (使い川, lit. ‘use river’), kawaba (川場 lit. ‘river place’), and so on; it was conveyed to either an indoor or an outdoor wet area (mizu-tsukai-ba 水使い場, ‘water use place’), as shown in the images below. In either case, there would be a simple shelf for storing pots, kettles, and other implements at the point of use. This facility is called the mizu-ya (水屋, ‘water roof/house’) in Shiga, mizu-goya (水小屋 ‘water hut’) in Tottori, kawa-dana (川棚 ‘water shelf’) in Saitama, kaidana (かいだな, prob. ‘river shelf’) in Gunma; in and east of Chūbu it is kawa-do (かわど, prob. ‘river place’), kawa-ba (かわば, ‘river place’), kado (かど), etc. In the ‘moat farmhouses’ (kangо̄ nо̄ka 環濠農家) of the Kita Kawachi (北河内) district of О̄saka Prefecture, the perimeter of the eave projecting from the moat-facing side of the main house (omo-ya 母屋) is enclosed to form a wet area, called the hinara (ひなら).

An indoor mizu tsukai-ba served by water that has been branched off from an outdoor source. Gifu Prefecture.

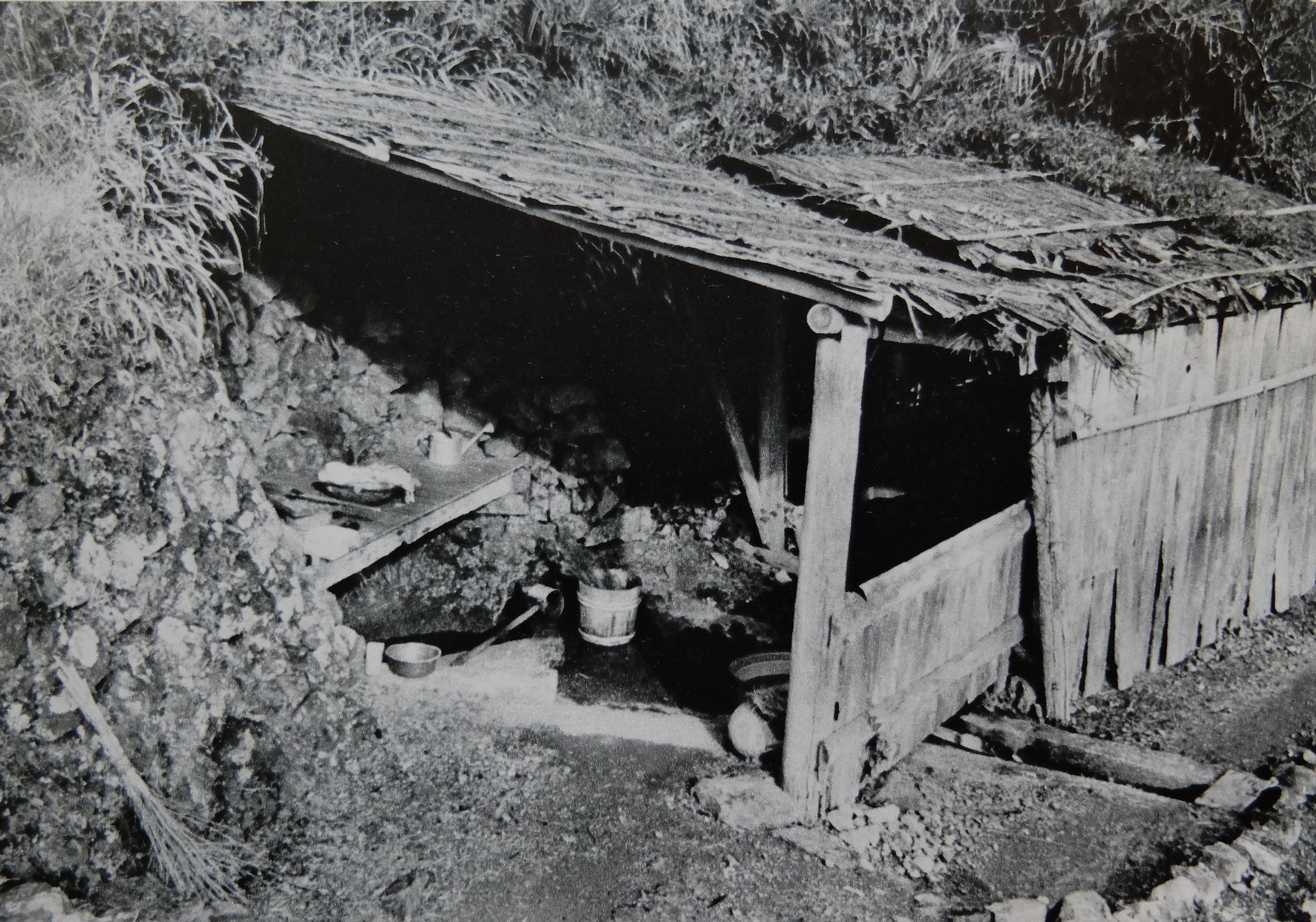

A mizu-ya (水屋, ‘water roof’) erected at the mizo-gawa in front of a house. There are shelves for pots and tableware, and preparatory cooking tasks are undertaken here, outdoors. In the main house there is only a jar (kame 甕) for drinking water. Shiga Prefecture.

The same mizu-tsukai-ba as shown above, in use. Shiga Prefecture.

In contrast to a communal spring, which is somewhat like a natural tap or faucet, where the source of water ‘upstream’ of the point of delivery is protected from pollution or despoilation by being underground, the quality of an exposed, surface-flowing water source such as a yо̄suiro cannot be preserved if every household that relies on it uses it however they please; in particular, downstream users can suffer from the actions of those upstream. So various regulations and etiquettes arose, just as they do when rivers flow through multiple states or countries. General wastewater was directed to a man-made pond (tame-ike 溜池), often used as a carp-breeding pond (yо̄ri-ike 養鯉池) or for some other productive purpose; rice water and urine were used as fertiliser; nappies (diapers) and underwear were washed in water drawn into a tub (tarai 盥) that was then emptied into a dedicated drainage channel. There were also rules relating to times of use: early mornings, for example, were reserved for drawing drinking water, and only after around 7am was it considered acceptable to use the water source for other purposes.

Management and use of a village’s water infrastructure was carefully planned and anticipated from the outset. The picture below shows an example in Gо̄barajuku (郷原宿), an old inn town in Nagano Prefecture. Water for general use (yо̄sui 用水, ‘use water’) flows in front of the roadside houses, while potable water is provided at communal, roofed wells built at regular intervals.

An example of water infrastructure planning: in the village of Gо̄barajuku (郷原宿), a roofed well providing water for drinking (inryо̄-yо̄ 飲料用) has been built, in accordance with the regulations, next to a yо̄suirо carrying general ‘use water’ (tsukai-mizu 使い水) for other purposes. Nagano Prefecture.

Below is an example from Fukui Prefecture. Flights of two or three stone steps are installed at the washing places (arai-ba 洗い場) in front of each house to provide access down to the yо̄suiro. In the winter months, such waterways function as ‘snow disposal gutters’ (ryūsetsukо̄ 流雪溝, lit. ‘flow snow gutter’), carrying away the snow that falls from roofs; they can often be seen in old towns and villages in the Hokuriku region.

Mizu-tsukai-ba established at a man-made ‘gutter’ (yо̄suirо 用水路) running in front of townhouses in a town in Mikata-chо̄ (三方町), Fukui Prefecture. A short flight of stone steps leading down to the water is visible in the lower right corner. This yо̄suirо also serves as a ‘snow disposal gutter’ (ryūsetsukо̄ 流雪溝) to carry away the snow that accumulates on roofs and in front of the houses.

Of the two methods of drawing from either natural or artificial sources of flowing water, those that use pipes (kan 管) are called kakehi-mizu (筧水 ‘pipe water’) or yama-mizu (山水 ‘mountain water’), and those that use open channels (mizo 溝) are called nagare-gawa (流れ川 ‘flowing river’), etc. Mizo is usually translated into English as trench, ditch, drain, channel, gully, gutter, etc., but these words can seem inadequate or inappropriate to describe something like that shown below: even today the water flowing in these waterways is often so clear and clean that aquatic plants, frogs, fish, and even sometimes fireflies can be found in them.

A yо̄suiro in Nishiwaki, Hyо̄go Prefecture.

In addition to ‘artificial’ water sources such as yо̄suirо, natural springs (waku-izumi 湧泉) were also heavily utilised, particularly in rural and mountainous areas. Springs may be, as in the image below, of the kiyo-mizu (清水, lit. ‘pure water’) type, where the water seeps out from the belly (hara 腹) of a mountain; or they may be of the type found in the Susono (裾野) region of Fuji (富士), Shizuoka Prefecture, where underground water flows out like a river to the surface.

A ‘water scooping place’ (mizu-kumi-ba 水汲み場), where spring water seeping out from the belly of the mountain is collected for use. Nara Prefecture.

This is not a normal mountain stream that has ‘picked up steam’ over a long distance from many small springs and streamlets feeding into it; it is groundwater that has emerged from a high-volume spring only a short distance upstream. Shizuoka Prefecture.

Below is a communal village mizu-tsukai-ba built at a moderately-sized spring in the foothills (sanroku 山麓) of the Yatsugatake (八ヶ岳) mountain range straddling Nagano and Yamanashi Prefectures. It is a social gathering place for the villagers; they have also expressed their gratitude for the water by enshrining the water deities (mizu-gami 水神) here.

A communal mizu-tsukai-ba built at a spring, enshrining the water deities; it is also indispensable as a social gathering place for the villagers. Nagano Prefecture.

Springs are called deshizu (出清水 ‘out pure water’) in Tо̄hoku and Hokuriku, kama (かま) in Chiba, demizu (出水 ‘out water’) in Chūgoku, and also kumi-kawa (汲み川 ‘drawing river’), tsubokawa (壷川 ‘pot river’), ike (いけ, ‘pond’), etc.; these names are used indiscriminately to refer to either piped or channelled water. There are many places where spring water (yūsui 湧水) is mainly used for drinking, as indicated by the name nomi-kawa (飲み川 ‘drinking river’); the water is drawn with a ladle (hishaku 柄杓) into water buckets (oke 桶) and carried back to each house to be stored in the large water jar (mizu-game 水甕) that sits beside the ‘sink board’ (nagashi-dai 流し台) in each house.

A glazed water jar (mizu-game 水甕), with wooden lid and ladle, stands next to the ‘sink board’ (nagashi-dai 流し台) in this diorama of the kitchen of a minka.