Previous posts in this series on minka layouts have been organised into sub-sections based on the number of rooms in the dwelling, progressing from single-space and one-room minka to two-room, three-room and four-room layouts. In this final subsection of the series, the focus will not be on the number of rooms but on one particular arrangement of them: the hiroma-type (hiroma-gata 広間型) layout, which has made many appearances in previous posts, but here I would like to examine it in some of its more elaborated forms.

The most prototypical expression of the hiroma-type layout is probably its three-room (san-madori 三間取り) variant, in which the hiroma, broadly definable as the ‘general habitable room’ of the minka, runs the full width of the dwelling, and is in the ‘lower’ position, adjacent to and fully bounding the doma; the other two rooms are ‘up’ from the hiroma and separated by it from the doma.

A typical three-room hiroma-type layout, with full-width multi-purpose habitable room (hiroma ひろま) in the ‘lower' position, and fully bounding the earth-floored utility area (here daidokoro だいどころ), ‘upper' front formal room (here oku おく), and upper rear bedroom (heya へや). The dot-dash line indicates the likely location of the partition line should the dwelling be converted into a four-room layout.

In all hiroma-gata layouts, the life of the dwelling is centred around the multi-purpose hiroma, whose main uses are generally dining and family gathering; the other rooms, be they the ‘formal room’ (zashiki 座敷), bedroom (nema 寝間), rooms for cooking (suiji 炊事) or work (sagyou 作業), all ‘serve’ the hiroma to some degree or other, but multi-room layouts where the rooms are arranged so that they ‘wrap around’ the greater part of the perimeter of the hiroma are known as tori-maki hiroma-gata (取り巻き広間型, lit. ‘wrapped hiroma type’ or ‘surrounded hiroma type’) layouts, to distinguish them from simpler three-room or four-room hiroma-type layouts. The wrapped hiroma type is common from the mountainous areas of the cold-climate Chūbu region (Chūbu chihо̄ 中部地方) to north-eastern Japan (Tо̄hoku Nihon 東北日本), probably because it has benefits for the purpose of warming the dwelling: heat from a large firepit (irori) in the central hiroma can radiate or convect more easily to the surrounding rooms.

The development path of the wrapped hiroma type can be seen in the plan diagrams below. First, in plan 1, a corner of the hiroma (ひろま) in a one-room dwelling is separated off as a bedroom (ne 寝). If the transverse partition (the partition parallel to the room-doma boundary) of this bedroom is then extended to the front wall of the dwelling, the result is a three-room hiroma-gata layout (2, lower plan); if the longitudinal partition (the partition perpendicular to the room-doma boundary) of the bedroom is extended to the edge of the doma, the result is a three-room front-zashiki (mae-zashiki 前座敷) layout (2, upper plan). Note that, interestingly, the ‘wrapped hiroma-type’ (plan 3) develops not from the three-room hiroma-type layout, but from the three-room front-zashiki layout. The use of zashiki (the ‘formal room’) in the name ‘front-zashiki’ can be somewhat deceptive, because in a three-room dwelling with this layout, the front room, regardless of name, functions primarily as the everyday ‘living room’ (hiroma); it can be commandeered as a space for receiving guests (sekkyaku 接客), but extending its functionally to include religious rituals (gishiki 儀式) and ceremonies (gyо̄ji 行事) is impractical. To fulfil these roles, an extension containing dedicated zashiki is added ‘upwards’ (上手 kamite) of the hiroma, resulting in the prototypical form of the wrapped hiroma layout (plan 3), with five rooms.

Plan diagrams illustrating the development of the one-room layout (1) into either a three-room hiroma-type layout (2, lower plan) or a three-room front-zashiki type layout (2, upper plan), and from there into a four or five-room wrapped hiroma type layout (3). Labelled are the earth-floored utility area (doma どま), the ‘living room' (hiroma ひろま), bedroom (nema, here ne 寝), formal room (zashiki, here za 座), and kagi-zashiki (鍵座敷).

Characteristic of the tori-maki hiroma-gata is that there are two or three small rooms to the rear of the hiroma, and that the zashiki upwards of the hiroma is a kagi-zashiki, meaning a zashiki occupying the upper rear quadrant of the habitable portion of the dwelling, making the layout ‘kagi-zashiki style’ (kagi-zashiki keishiki 鍵座敷形式). In the Tо̄hoku (東北) region, this style is the mother layout of the many chūmon zukuri (中門造り) and magari-ya (曲り屋) L-plan minka found in that area.

Real-world examples of the plan diagrams 1 and 2. On the left (1), a reconstruction of the original plan of a very old minka in Sakata (阪田), Hyо̄go Prefecture (Hyо̄go-ken 兵庫県), showing earth-floored utility area (doma どま), board-floored (ita-yuka 板床) general habitable room (hiroma, here called hiroshiki ひろしき), and bedroom (nando なんど). On the right (2), a farmhouse (nо̄ka 農家) in Arasawa village (Arasawa-mura 荒沢村), Iwate Prefecture (Iwate-ken 岩手県), showing earth-floored utility area (niwa にわ), large stable (maya まや), board-floored general habitable room (jо̄i じょうい) which also functions as the formal room (zashiki) and contains a firepit (hibito ひびと), Buddhist altar (butsudan, marked manji 卍) and shrine (kami-dana 神棚), walk-in closet (mono-oki ものおき), and bedroom (nebiya ねびや).

A real-world example of plan diagram 3, a wrapped hiroma L-plan (magari-ya 曲り屋) minka in Iwate Prefecture. Labelled are the central hiroma, here called the chanoma (ちゃのま), the ‘lower zashiki' (shita-zashiki したざしき), the ‘upper zashiki' (kami-zashiki かみざしき) with decorative alcove (toko とこ), the bedrooms (nando なんど and heya へや), the utility area (niwa にわ), and the kitchen (daidoko だいどこ) with firepit. The magari-ya (the front leg of the L) is partly omitted.

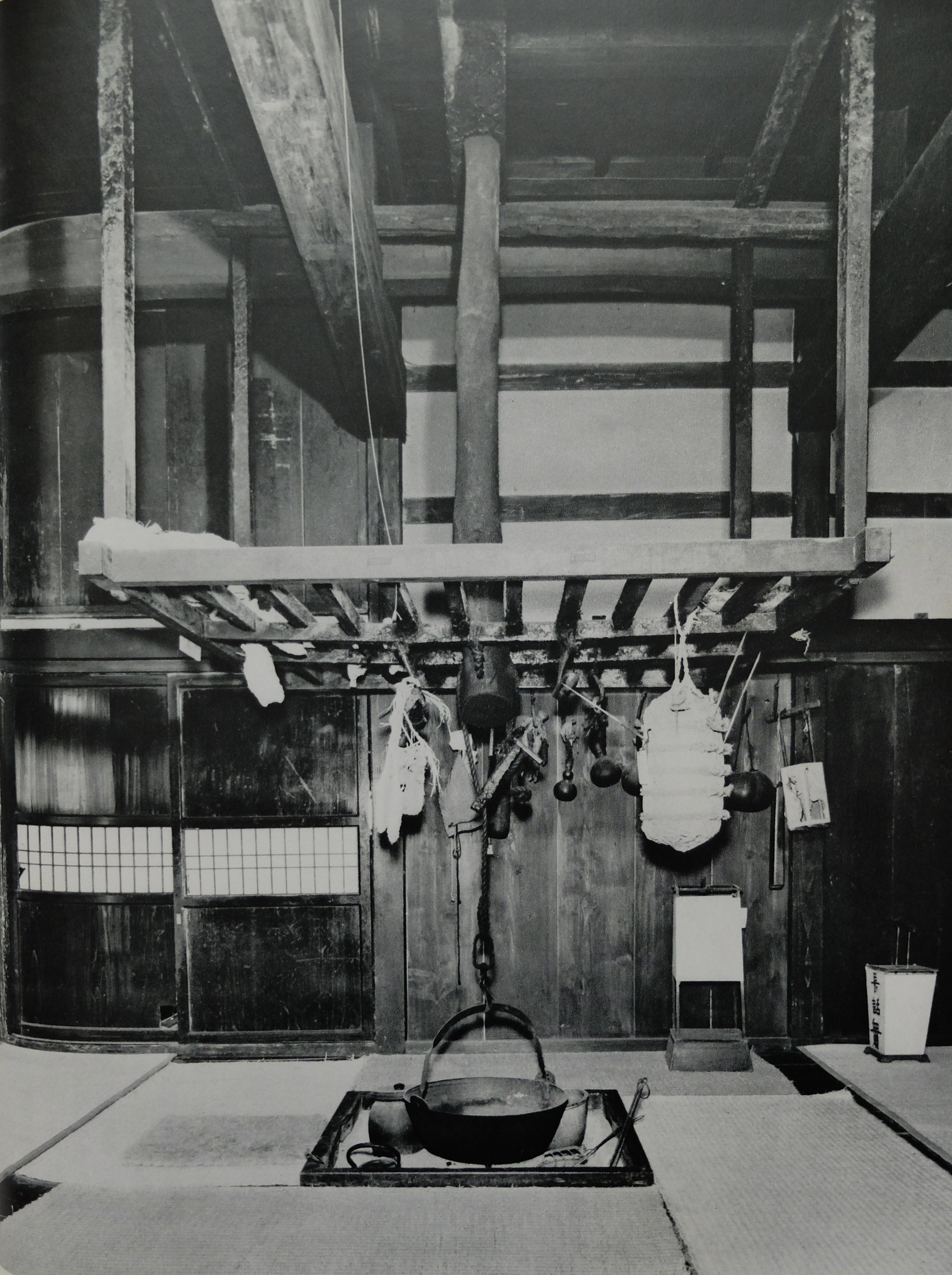

Interior view of the hiroma (here called the omē (おめえ) of a minka with a wrapped hiroma type layout in Yamagata Prefecture. The hiroma has a central firepit (irori 囲炉裏) and is in turn the centre of the dwelling, with the zashiki and bedrooms wrapped around it.