In a previous post in this series on four-room layout (yon-madori 四間取り) minka, we discussed the two types of staggered layout: the perpendicular stagger type (yoko-kui-chigai kata 横食違い型) and parallel stagger type (tate-kui-chigai kata 縦食違い型). Here we will wrap up this series on four-room minka by comparing two final examples, one of each type of staggered layout.

The mode of habitation differs between these different layouts. Certain layouts are generally more common in snow country and in mountain villages: kagi-zashiki (鍵座敷, lit. ‘key zashiki’, meaning a zashiki located at the upper rear corner of the dwelling) layouts; layouts where the ‘kitchen-dining room’, often called the katte (勝手), is large in comparison to the ‘living room’, often called the dei (でい); and layouts where the rear of the earth-floored utility area (doma 土間 or niwa にわ) is divided off, board-floored, and equipped with a firepit (irori 囲炉裏) to become a large katte.

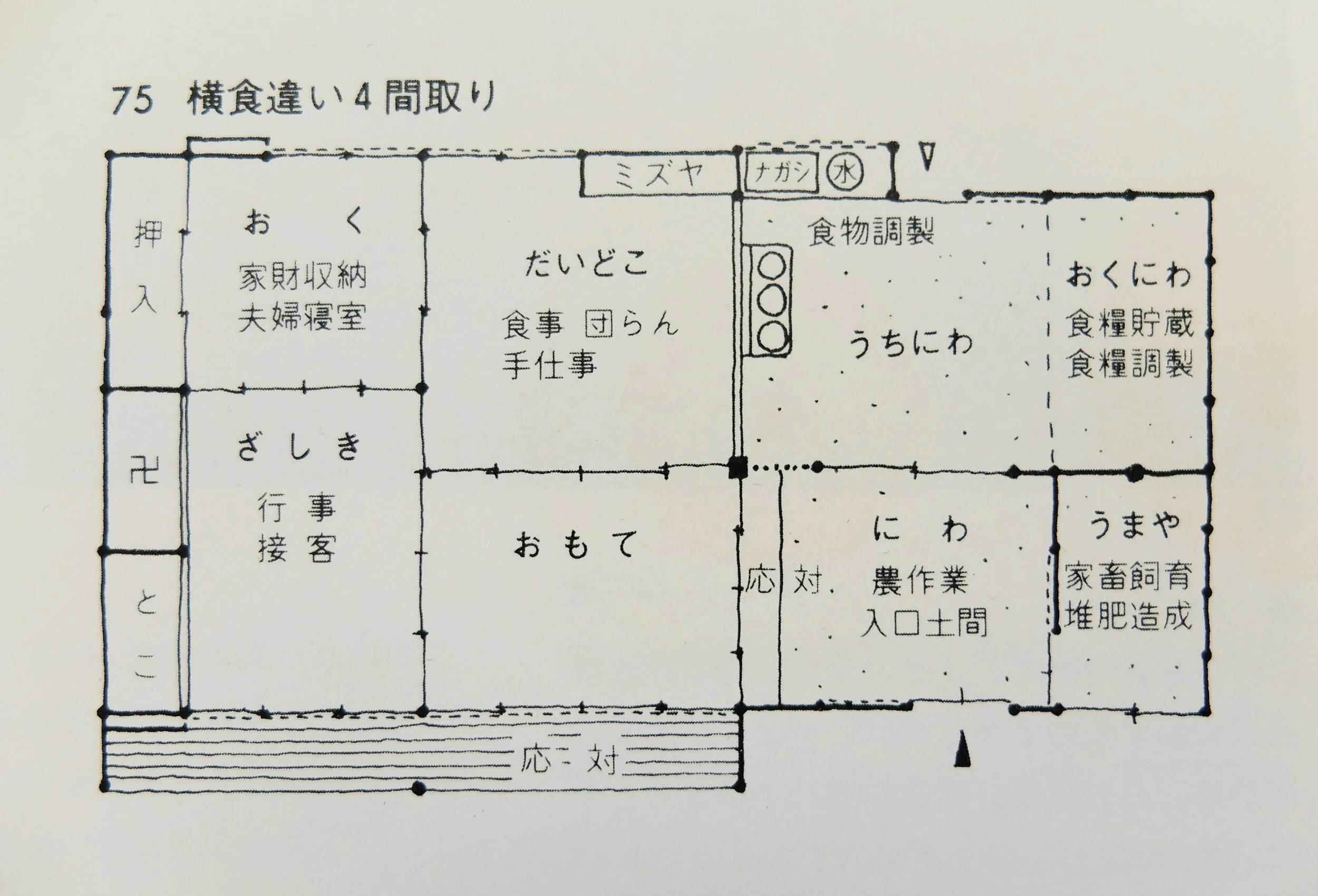

The two plans shown below are both staggered four-room layouts. The first, the Komaki family (Komaki-ke 小牧家) residence in Ibo County (Ibo-gun 揖保郡), Hyо̄go Prefecture, is a yoko-kui-chigai (横食違い) or ‘perpendicular stagger type’; the other, the Kobayashi family (Kobayashi-ke 小林家) residence in Kita-kuwada County (Kita-kuwada-gun 北桑田郡), Kyо̄to Prefecture, is a tate-kui-chigai (竪食違い) or ‘parallel stagger type’.

Besides the mode of stagger, there are other points of difference: the Komaki house has a more ‘modern’ open bedroom (nando なんど), meaning that the nando partitions consist entirely of operable sliding fittings, so the room can be fully opened up to the rest of the interior and used for other purposes, which necessitates a closet (oshi-ire 押入) for hiding bedding and clothes away during the day. This style is common among lowland minka on the plains regions (heiya-bu 平野部) of Japan.

In contrast, the Kobayashi house has a closed nando, with fixed walls and only a single sliding entry door; this is more characteristic of older minka and minka in the mountainous areas (sankan-bu 山間部) of the country.

Recall that layouts in which the decorative alcove (tokonoma 床の間) is on the end wall, i.e. the ‘gable wall side’ (tsuma-gawa 妻側), are called tsuma-toko keishiki (妻床形式), and those where it is on the long wall side (hira-gawa 平側) are called hira-toko keishiki (平床形式), lit. ‘long alcove style’. Both the Komaki house and Kobayashi house are tsuma-toko layouts; in the Komaki house both gable-end walls are blind (without openings), which is characteristic of minka from this area, whereas the Kobayashi house has one blind gable-end wall, and the other end contains a utility entrance and a window.

In both houses, the daidoko (だいどこ), the everyday gathering place of the family, is the room that has gained area from the stagger to become the largest room, and so has direct access to all three other rooms. This is not always the case: there are also staggered layouts in which the daidoko loses area from the stagger to the ‘front room’ (omote-no-ma おもてのま), or even to the nando.

The Komaki house in Ibo County (Ibo-gun 揖保郡), Hyо̄go Prefecture. A perpendicular stagger type (yoko-kui-chigai kata 横食違い型), facade zashiki type (omote-zashiki gata 表座敷型), ‘gable alcove style' (tsuma-toko keishiki 妻床形式) four-room layout, with an ‘open' bedroom (nando, here called oku おく). The earth-floored utility area (niwa にわ) is highly developed, also displaying a four-part division: the niwa proper with entry area (iriguchi doma 入口土間) and long, deep ‘step' for greeting/receiving visitors (о̄tai 応対), for agricultural work (nо̄-sagyо̄ 濃作業); the stable (umaya うまや) for raising livestock (kachiku shi-iku 家畜飼育) and composting (taihizо̄sei 堆肥造成); the ‘inner niwa' (uchi-niwaうちにわ) with rear entrance, stove, sink (nagashi ナガシ) and water (mizu 水), for food preparation (tabemono chо̄sei 食物調整); and the ‘rear niwa' (oku-niwa おくにわ) for food storage (shokuryо̄ chozо̄ 食糧貯蔵) and food preparation. The four rooms are the dining-family room (daidoko だいどこ), unpartitioned from the uchi-niwa, with ‘tea service' (mizuya ミズヤ), for dining (shokuji 食事), family time (danran 団らん), and handwork (te-shigoto 手仕事); the open bedroom (oku おく) for storage of family possessions (kazai shūnо̄ 家財格納), and husband and wife sleeping (fūfushūshin夫婦就寝), with closet (oshi-ire 押入); the formal zashiki (ざしき) for ceremonies (gyо̄ji 行事) and receiving guests (sekkyaku 接客), with decorative alcove (toko とこ) and Buddhist alcove (butsuma 仏間, marked 卍); and the omote (おもて), somewhat between the daidoko and the zashiki in its level of formality, for receiving visitors (о̄tai 応対) both from the niwa and from the verandah (engawa).

The Kobayashi house in Kita-kuwada County (Kita-kuwada-gun 北桑田郡), Kyо̄to Prefecture. A parallel stagger type (tate-kui-chigai kata (縦食違い型), front/facade zashiki type (omote-zashiki gata 表座敷型), ‘gable alcove style' (tsuma-toko keishiki 妻床形式) four-room layout. The narrow niwa (にわ) has entry area (iriguchi doma 入口土間), mortar (kara-usu カラウス), stove (kudo くど), sink (hashiri ハシリ), and water (mizu 水), and is for storage (chozо̄ 貯蔵), food preparation (tabemono chо̄sei 食物調整), feed preparation (shiryо̄ chо̄sei 飼料調整), and agricultural work (nо̄-sagyо̄ 濃作業). The four rooms are the dining-family room (daidoko だいどこ), unpartitioned from the niwa, with shelves (tana 棚) and firepit (irori, marked ro 炉), for dining (shokuji 食事), family time (danran 団らん), handwork (te-shigoto 手仕事), and entertaining guests (о̄tai 応対); the ‘lower room' (shimo-no-ma しものま) which is for receiving guests (sekkyaku 接客) and also functions as a ‘break-out room' for religious (shinkо̄ 信仰) ceremonies or other events (gyо̄ji 行事) held in the formal ‘upper room' (kami-no-ma かみのま); the kami-no-ma contains a decorative alcove (toko とこ) and Buddhist alcove (butsuma 仏間, marked 卍) in the gable wall and is also used for sleeping (shūshin就寝); and the closed bedroom (nando なんど) for storage of family possessions (kazai shūnо̄ 家財格納) and husband and wife sleeping (fūfushūshin夫婦就寝), without a closet (oshi-ire 押入). The verandah (engawa) is for receiving visitors (о̄tai 応対) and handwork, and contains a storage closet.

Exterior view of an old thatched minka in a mountainous area of Tanba-guchi (丹波口), Kyо̄to Prefecture. Like the Kobayashi house, it has a staggered four-room interior layout with a ‘quarantined' nando.

The contrast in ‘atmosphere’ between these two interior layouts, in particular that between the two styles of nando, seems to reflect the contrast between their respective environments: the close, dark mountain forest versus the open, airy plain.