In this entry on two-room layouts (ni-madori 二間取り), we will consider a few examples of mu-doma taka-yuka keishiki (無土間高床形式), or ‘no-doma raised-floor type’ two-room minka, in which there is no earth-floored utility area (doma 土間). In its place, there is a raised-floor (taka-yuka 高床) space that fulfils all the functions of the doma; unlike the doma, however, this space also hosts ‘non-utility’ activities such as dining, and is thus considered a fully-fledged room and counted as such when it comes to classifying a plan-form.

The plan below, from the mountainous Iya (祖谷) district in Shikoku, is a ‘transverse division’ (tate-bunwari 竪分割), ‘longitudinal lineup’ (heiretsu-gata 併列型 or 並列型) two-room plan-form (ni-madori 二間取り). It consists of a ‘dining-kitchen’ room called the uchi-no-ma (うちのま) and a zashiki-like room called the omote-no-ma (おもてのま) that combines the functions of ‘living room’ (omote) and ‘formal room’ (zashiki). Without a doma, entry is instead via the board-floored ‘verandah’ (kiri-en 切り縁) running the full length of the front/façade side of the building. There is a full partition between the two rooms, and the ‘living functions’ (seikatsu-naiyou 生活内容) of the uchi-no-ma are substantial, qualifying this as a true two-room dwelling. Both rooms contain a firepit (usually irori いろり, in the local dialect yururi ゆるり).

A ‘transverse division’ (tate-bunwari 竪分割) ‘longitudinal lineup’ (heiretsu-gata 併列型 or 並列型) two-room plan-form (ni-madori 二間取り) from the Iya (祖谷) district in Shikoku. The 15-mat (approx. 25m²) uchi-no-ma (うちのま) is counted as a room. It contains the firepit (yururi ゆるり), sink (nagashi ナガシ), water (mizu 水), tea preparation area (mizu-ya 水や) and stove (kamado かまど). The 12.5-mat (approx. 20m²) ‘living room’ (omote-no-ma おもてのま) contains another firepit, closets (oshi-komi 押込み), Buddhist altar (marked 卍), and Shinto ‘shrine’ (kami-dana 神棚). On the ‘verandah’ (kiri-en 切り縁) are the bathing area (mokuyoku-jо̄ 沐浴場) and toilet (benjo 便所).

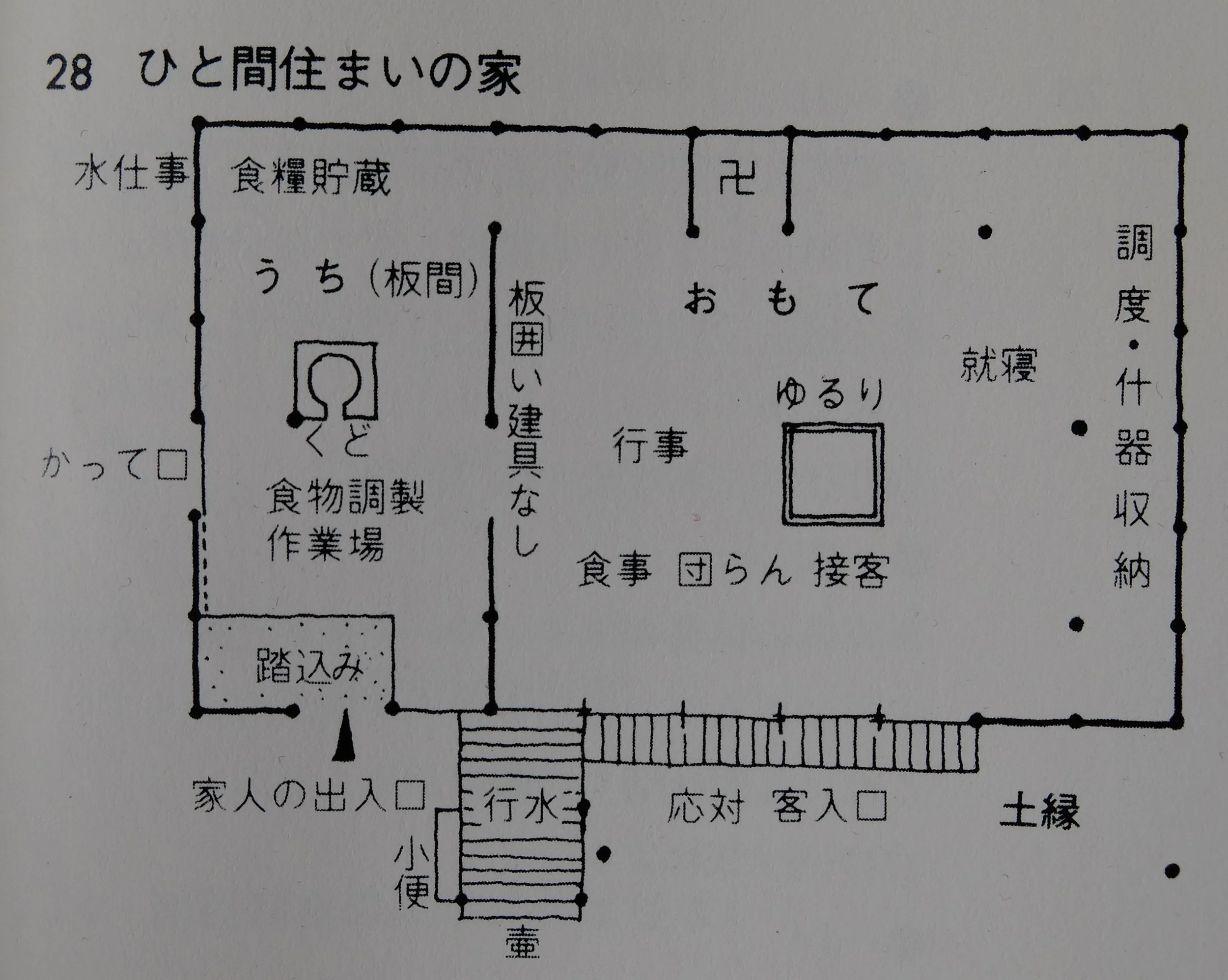

Compare the plan above with another fully board-floored minka covered in a previous post on one-room dwellings (hito-ma sumai ひと間住まい), shown below. Here, although the doma equivalent (in this case called the uchi うち) is a board-floored space (ita-ma 板間), it hosts only utility activities, and there is only a board screen (ita-kakoi 板囲い) between the uchi and the omote (おもて), not full, operable fittings (tategu 建具). For these reasons it is classified as a one-room layout (hito-ma dori ひと間取り or isshitsu-gata 1室型).

A one-room (hito-ma dori ひと間取り) minka with a board-floored (ita-ma 板間) ‘doma’ (here called the uchi うち) that is not counted as a room.

An unusual feature of minka in the Iya area is that the toilet (benjo 便所) and bathing place (mokuyoku-jо̄ 沐浴場) are given prominent position in the middle of the south-facing façade, which may seem irrational to anyone accustomed to wet areas being hidden away on the dark side of the house. Perhaps this was the result of the desire for sunlight (hygiene) and warmth, or to avoid having to route wastewater away from the upslope side of the house, or to obtain the floor-to-ground height necessary for a ‘drop’ or pit toilet and make collection of waste more convenient. The original conditions that motivated it may have been long forgotten by the time these minka were surveyed in the mid-20th century, with the plan-form surviving due to the inertia of custom.

Exterior of a longitudinal lineup (heiretsu-gata 併列型) three-room (san-madori 3間取り) minka in the Iya district of Shikoku. The toilet (benjo 便所) and bathing place (mokuyoku-jо̄ 沐浴場), given privacy by only a basic privacy screen, can be seen projecting from the facade.

On the northern, ‘mountain side’ of these minka there is a narrow interior space formed between the rows of inner posts (jо̄ya-bashira 上屋柱) and outer posts (geya-bashira 下屋柱). Storage (oshi-komi 押込み), Buddhist altars (butsudan 仏壇), Shintо̄ shrines (kami-dana 神棚, lit. ‘god shelf’) and even small bedrooms (shinshitsu 寝室) might be inserted into these spaces, in accordance with the post spacing (hashira-wari 柱割り).

With rising individual fortunes and general progress over time, many of these two-room minka developed into three-room ‘longitudinal lineup’ (san-shitsu heiretsu 三室併列) layouts, and then eventually into staggered (kui-chigai 食違い) or regular (seikei 整形) six-room layouts (roku-madori 六間取り).

Example of the transformation of a ‘longitudinal lineup’ two-room layout (ni-madori 2間取り) minka (first plan) in the Iya district into a longitudinal lineup (heiretsu-gata 併列型), three-room (san-madori 3間取り) then four-room layout, with separate bedroom/s, then into a staggered (kui-chigai-kata 食違い型) six-room (roku-madori 6間取り) layout, and finally into a regular (seikei 整形) six-room layout (roku-madori 6間取り).

In the mansions and villas (yashiki 屋敷) of the upper classes, complex layouts provisioned with formal entry ‘vestibules’ (genkan 玄関) and ‘upper rooms’ (jо̄dan-no-ma 上段の間, formal rooms whose floor level is a step above that of the regular rooms) can also be seen.

A jо̄dan-no-ma (上段の間) in an upper-class residence.