After covering several varieties of magari-ya in last week’s post, today I will look at another general minka type, the futamune-zukuri (二棟造り), or ‘two ridge’ minka. As the name suggests, these minka are basically two structurally independent buildings; they may be either entirely separate, requiring one to go outside when passing between them, or joined to some extent. They are most commonly found in the southern regions of Japan, from Okinawa to southern and central Kyushu. The two buildings of the whole are the hon-ya (本屋), the ‘main house’ with raised floor for living, sleeping, etc., and the earthen-floored oto-ya or ‘cookhouse’, (lit. ‘pot/cauldron house’ 釜屋); they are roughly the same size, and are arranged either with their ridges parallel (the formal name for this arrangement is 平行二棟式, heikou-futamune shiki ‘parallel two ridge type’) or at right angles to one another.

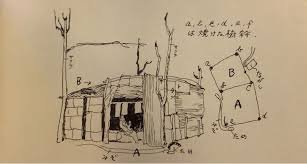

Example of a ie-nakae secchaku minka with the ridges of each building arranged at right angles to each other.

It’s not difficult to understand why this type of minka is found predominantly in southern Japan. In subtropical climates like Okinawa and southern Kyushu, separating the ‘cooking’ and ‘living/sleeping’ functions of a house into two separate buildings means that heat from the stove can be kept out of the main dwelling; another advantage of isolating the hon-ya from the oto-ya is that in the event that the oto-ya is destroyed by fire, the hon-ya will stand some chance of surviving (depending on the wind direction of course!). The scale of these dwellings tends to be quite modest; another advantage of the two-ridge type might have been that the two buildings can be completed in two stages, as funds become available. And of course, as with any vernacular building form, we shouldn’t overlook the cultural factors behind the evolution and persistence of any particular typology or design element, i.e. “that’s the way it’s always been done.”

The ie-nakae secchaku (イエ・ナカエ接着) is one name for a variant of the two ridge minka in which the two building volumes (here termed the ie and the nakae) touch (secchaku) at their eaves, and are joined below by walls to form a relatively unified interior space. The ie, or sometimes omote, are regional variant names for the hon-ya; the nakae is the oto-ya.

Map showing the distribution of various configurations of ie-nakae secchaku minka on the Satsuma Peninsular, southern Kyushu

Where the two roofs meet, a box gutter is provided. In our era when long lengths of sheet metal are cheap and readily available, box gutters are taken for granted; in pre-industrial times constructing a waterproof box gutter was a much more impressive technical feat, using only split bamboo, or perhaps a hollowed-out half-log.

Ie-nakae secchaku minka, showing the box gutter and infill wall where the two buildings meet. The box gutter is a combination of old and new: the (presumably original) technique of split bamboo cleverly lashed together into a kind of Spanish tile arrangement, with the upper convex ‘capping’ sections of bamboo directing water into the lower concave ‘gutter’ sections; and the modern addition of cheap and timesaving sheet metal to make the old bamboo waterproof rather than replace it.